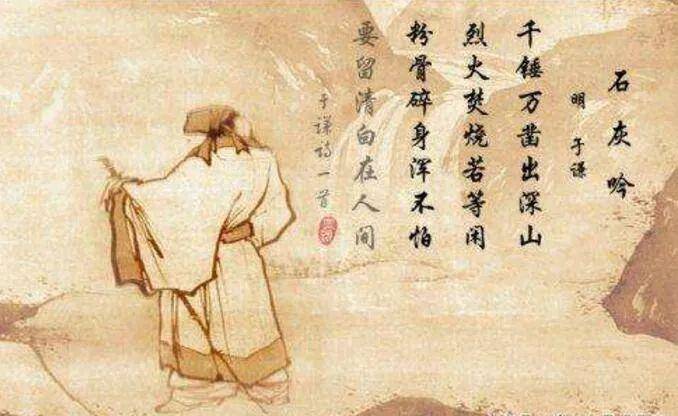

The Limestone Rhyme

- Poetry of Yu Qian

Pounded, chiselled myriad times, deep in the hills I was mined;

Be burned and blazed in raging fire is but nothing, to my mind.

My bones be crushed, body severed, shall brave it all, and more,

To leave behind an impeccable white to remain with humankind.

Translated by Andrew W.F. Wong (Huang Hongfa)

*粉身碎骨 (“torn bodies and crushed bones”) is an idiom, meaning “to sacrifice one’s life”

Yu Qian’s use of the steadfast limestone as an extended metaphor for himself illustrates his determination to leave behind purity and innocence regardless of the obstacles he will face. On the surface, this poem seemingly describes the simple process of extracting limestone from the mountains; upon deeper investigation, the poet alludes to various tribulations from his personal history. The first four words, 千锤万凿 (countless hammerings and chiselings), emphasize the workers’ use of numerous poundings to extract limestone from the mountains; similarly, Yu Qian felt hammered down by Emperor Zhengtong, who accused him of being a traitor even after Yu restored peace and stability following an invasion. Faced with unjust exploitation, Yu finds solace in knowing that he is not alone in his suffering–the limestone faces similar trials. The phrases 等闲 (to give no care) and 不怕 (to have no fear) hint at the limestone’s personality: it does not fear being burnt or crushed because it recognizes its own blamelessness. In the end, the limestone knows that it will only leave behind 清白 (white purity) in the corrupted human world. Likewise, Yu Qian would rather die with virtue than live with wrongdoing.

千锤万凿出深山,烈火焚烧若等闲。

粉骨碎身浑不怕,要留清白在人间。

- Why Chinese poems is so special?

- The most distinctive features of Chinese poetry are: concision- many poems are only four lines, and few are much longer than eight; ambiguity- number, tense and parts of speech are often undetermined, creating particularly rich interpretative possibilities; and structure- most poems follow quite strict formal patterns which have beauty in themselves as well as highlighting meaningful contrasts.

- How to read a Chinese poem?

- Like an English poem, but more so. Everything is there for a reason, so try to find that reason. Think about all the possible connotations, and be aware of the different possibilities of number and tense. Look for contrasts: within lines, between the lines of each couplet and between successive couplets. Above all, don't worry about what the poet meant- find your meaning.